The Lost Art of Parliamentary Eloquence: From Pitt to the Present

It is clear that I have, if not an academic, then a personal obsession with the life and career of William Pitt the Younger. Besides, I am doing my second-year History Research project on our youngest Prime Minister, so forgive me if I ask you to indulge me for a moment. As Evans writes in his biography of the latter, “William Pitt is well worth the effort to understand…Pitt was a leader of great gifts who, at the height of his powers, exercised a dominance over both parliament and his monarch which very few Prime Ministers have equalled”. (Evans, 2002, p2)

Pitt failed to cultivate a life outside of politics, and it is perhaps because of this that we know him as someone who not only occupied the office of First Lord of the Treasury but made it his own to the extent that he is now regarded as the first modern Prime Minister. It is not, however, this remarkability which I am writing about. From an early age, Pitt was a prodigy. Son to one of the most eloquent and passionate parliamentarians to have sat in the Commons, Pitt wielded a “sharp intellect, highly advanced powers of speech and memory, and a clear interest in public affairs”. (Hague, 2005, p14-15) His father, Pitt the Elder (later the Earl of Chatham) raged against the Stamp Act in the Commons and wrote to Pitt’s mother “I expect many sage reflections from William on the public papers” when he was just 8 years old. (Hague, 2005, p15) These “highly advanced powers of speech” would first be witnessed by trees posing as Members of Parliament for the young Pitt on his father’s estate4 however, at the height of his unprecedented power as Prime Minister, Pitt “exercised to its full range the natural speaking ability which his father’s tuition had extended until it was extraordinary”. (Hague, 2005, p583)

Pitt’s own rise coincided with that of parliamentary oratory, to its highest standard in history. The historian Macaulay once wrote that “Parliamentary government is government by speaking. In such a government, the power of speaking is the most prized of all qualities which a politician can possess”. Knowledge of the importance of oratorical style is something that has guided all leading political heavyweights, from Cicero to Pitt, Gladstone to Churchill, Castle to Boothroyd. (Meisel, 2001, p51) By 1913 however, the style wielded in the cramped chamber by the likes of Pitt and Gladstone was dying. Lord Curzon was certainly right when he said that Churchill was the last of a dying breed, the last of a generation, “who still cultivates, I will not say the classical, but the literary style, and at times practises it with great ability”. (Meisel, 2001, p51)

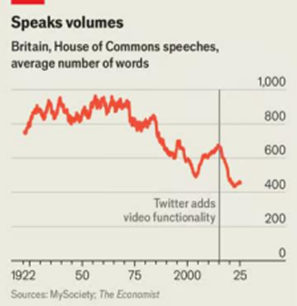

Gladstone’s speeches occupy 18,000 columns of Hansard and appear in over 366 volumes. (Rogers, 2012) Last year, speeches in parliament barely reached 500 words. (The Economist, 2025) The Economist (2025) has lamented the decline in parliamentary oratory, writing that it is a crucial part of our democracy:

“Debate defines who becomes a politician: a list of former presidents of the Oxford Union is a “Who’s Who” of British politics”

While eighteenth century parlance may be a reason as to why we find today’s speeches eclipsed by the oratory of giants such as Pitt, Fox, Gladstone and Churchill, the days of singing in the House are most definitely over. At the age of seven, Pitt the Younger would write letters in Latin to his father, and in English adopted a pompous, wordy, convoluted style. (Hague, 2005, p9) Whilst language will always change, it is sad that we will never hear classical oratory in parliament again, that has been lost to history. We live in an age of abbreviations, simplification and It is also a great tragedy that parliamentary proceedings were scarcely documented at the time of both the Elder and the Younger. (Hague, 2005, p9) Nevertheless, I’ll stop whinging.

Whilst classical and literary styles are a thing of the past, I hope to see a return of, to quote a scene from Peaky Blinders, singing like a songbird in the House.

Bibliography:

Evans, E. J. William Pitt the Younger. London: Routledge, 2002.

Hague, William. William Pitt the Younger. London: Harper Press,2005 Rogers, Robert. Who Goes Home. London: Biteback Publishing, 2012.

Meisel, Joseph S. "The House of Commons." In Public Speech and the Culture of Public Life in the Age of Gladstone, 51–106. New York: Columbia University Press, 2001.

The Economist. "Speeches in Britain’s Parliament Are Getting Shorter—and Worse." The Economist, February 3, 2025. Accessed March 30, 2025. https://www.economist.com/britain/2025/02/03/speeches-in-britains-parliament-are-getting shorter-and-worse.